The Second part of my recent interview with Frank B. Wilderson, University of California Professor and author of the Books Incognegro, and his most recent Red, White and Black, Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms took part after a live reading/discussion he did of both books at the University of California Davis in late May. It is important to call out the proverbial 10,000,000 pound elephant in the room regarding this interview without being apologetic. This discussion was punctuated by the idea and flavor of struggle, and for the reader to benefit completely from it (the conversation), they must be willing to engage in a process of struggle.

There is theorizing here concerning the role of Black flesh in human history that could be considered disturbing, or even evocative of widening a schism between black and white, but that is not the purpose or intent of the theorizing. The purpose and intent is to describe in unfettered terms, a very difficult truth concerning an historical and systemic, oppressive and negating dynamic regarding the very idea and reality of Blackness in the world.

Human beings often define themselves according to the quantity, quality, and dramatis of their suffering, but I don’t think this is what Frank and I were discussing here. This is about trying to make sense of it all. This is about posing the essential questions that could lead to…the end of the world as we know it……So please read and capture the discussion with the spirit in which it was intended. Join the discussion, post your comments, I’d really like to hear back from people speaking from their hearts concerning all that’s here.

Besides all this we also discuss Oprah, Public Enemy, Expectations of Black Comedians, PTSD, and the particular struggles Black and White Therapists have in engaging with their clients. Read On.

PH Frank, your new book Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms is as much a philosophical foundation for a way of looking at the necessity of revolution of some sort as concerns relationships between Blacks and Whites in America as it is a study of the impact of the implicit coding of films concerned with race. Can you elaborate a little bit on that?

FW Um, the necessity of revolution?

PH Of some sort…In your writing, in both books, you basically call people to a point of going beyond looking at race relations as simply figuring out how to get along, which is not enough.

FW I see what you’re saying.

PH What is the next step? There must be some sort of revolutionary impetus involved, and I only use that term because I don’t really know another one.

FW Yeah, I hear you. And I’m often….not often but sometimes afraid of the political implications of what I say.

PH That’s understandable.

FW Yeah. Orlando Patterson wrote a book called “Slavery and Social Death”, and I’m not sure Patterson would agree with where I’ve taken this but what I like about his book is he says that work is an experience of slavery but it doesn’t define slavery. He says that slavery is general dishonor, that the being is dishonored regardless of what he or she does natal alienation of the being whose family ties or kinship structure in his or her mind is not respected by anyone else. (Slavery is also punctuated by) openness to gratuitous violence, which is a body that you can do anything with. And what interests me is that if that becomes the definition of a slave, the slave can work, but the slave can also sit on a divan and eat bon-bons.

PH Absolutely.

FW You know? In my hometown of New Orleans in the days of physical slavery you could buy the slave to inject them with poisons to watch them die. So what’s interesting to me is that, as I was saying earlier today, there’s a way in which the Arabs and the Europeans came to a consensus (not sitting down at a table but over years), that Africa is a place where people are generally dishonored, where we do not respect their kinship structures and where their bodies are available to us to do to them whatever we would. This has been our (Black people’s) place ever since then. Once I got to that and started thinking that through it occurred to me that cinema was just another place in which the Black Body was possessed and deployed in the way that one would possess and deploy a slave in any other context.

PH Right.

FW And that there is no reformist program for ridding ourselves of that. I mean, it’s like if we’re gonna get out of that we’re gonna be in a whole new world order.

PH Right. And it’s interesting because you look at film as just a context, a context for this process to occur. You know, one can I think Say the same thing about the NBA.

FW Exactly, yeah.

PH It brings back the scenario in which the slave can eat bon-bons and make $20-million a year.

FW Exactly, exactly.

PH But you’re still a slave, because to me, that really sort of encapsulates the whole conceptualization of fungibility.

FW I mean, that came home years ago to me. And I don’t remember, I think it was Cleveland, where fans were so happy when the Blacks are performing on the court and when they were not, then when they threw garbage at the court.

PH Steve McNair syndrome.

FW Yeah.

PH Steve McNair in Houston. You know, he was the hero of the town but you know, when things weren’t going well you know…nigger, he’d hear it every day.

FW Man.

PH I think your book brings this point out in sort of stark relief, in an unemotional way, which I can certainly appreciate, and which is necessary. During your talk today (at U.C. Davis) you talked about the fact that we don’t have the cognitive mapping to discuss the issue correctly.

FW Right, right.

PH So I think books such as what you’ve just written are a good step in the direction of at least of mapping out the issues. Whether people can respond unemotionally and thoughtfully to these hypotheses is another thing.

FW Yes.

PH I’ve got another question here, but I’m going to chop off the second part of it.

FW Okay.

PH I’m actually going to skip right over it. It seems to me that part of the ongoing entrenchment concerning the master slave dichotomy is self-imposed upon us. Black people willingly accepting the role as allegorical slave for certain rewards, we’ve been speaking of a little bit. I think this is an operational reality when it comes to Blacks in the entertainment industry in general. What are your thoughts about how and why this occurs? What do you think attributes to this process?

FW I think it’s such a deep problem that it’s even hard to go ahead and think about, but we’ll try here. One of the things I didn’t get as deeply into in my book as I would have wanted to would be the work of a Black psychoanalytic scholar named David Marriott who’s down at UC Santa Cruz. And I’m not sure I have the time to do the heavy lifting of reading all his work right now, but what I can say is that he has this theoretical intervention about the unconscious which suggests that the Black unconscious is always at war with itself because it shares something with the White unconscious which is a hatred for the Black imago, for the image of the Black. I hope I can do the theory justice because I use his work in my film book but I don’t use it in the breadth and the depth that he has written in his books. He’s not trying to condemn Black people for an unconscious that has as a constituent element hatred of blackness, but he’s trying to suggest that there is violence in the world which is coordinated with Negrophobia. There’s the fantasy of a Black as a phobic object, an object that will destroy you and you don’t even know how it will destroy you, just an anxious threat, you know. And he says, okay, that’s a fantasy, but what’s important, what psychoanalysis hasn’t really figured out, is that what’s important about this fantasy is that it is supported and coordinated with all the guns in the world…

PH Uh-huh.

FW And I, the Black, can have a fantasy of white aggression, but it is not coordinated with any institutional power.

PH Right.

FW And he says if you go through generations, that it’s really not immediately possible for you to simply genocide that unconscious hatred of yourself because the hatred of Black, of the Black, is also fundamental to being accepted in society. So he’s saying that there is, that there’s two things happening in the Black unconscious, one is a hatred of the Black, of aggressivity towards the Black imago which is the same aggressivity that society has, so that Denzel Washington can say at the end of Training Day “I’m King Kong”, you know. You know, my God. You know?

PH I actually laughed out loud, it was just ironically bitter when he said that in the movie, yeah.

FW Shut up!

PH I know.

FW My God.

PH I’m King Kong!

FW I’m King Kong! So that’s necessary to live in the world. And it’s like damn, you’re faced with this, like I said today, every Black person in Africa was incorporated into the question of captivity. That’s really intense.

PH Yeah it is.

FW To have a whole continent of people having to negotiate captivity.

PH Uh-huh.

FW That’s something no other people in the world have ever had happen to them.

PH Right, right (Editorial comment: With the possible exception of the Jews during the time of Egyptian captivity and exile….another subject for a later discussion).

FW So one of the ways that people tried to negotiate that is to find a way to the side of non-captivity which is “how can I be a good white negro?” You know, I would be remiss if I said that I don’t have those thoughts…From time to time, everybody does, you don’t get promoted, I mean, your promotion at work is based on the degree to which you can embody that

PH We have gotten to the point to where, in my opinion, there’s this weird thing that’s happened to where the dynamic has sort of flipped back on itself in the entertainment industry in the sense that, let’s just say you’re 50 Cent, you know, he embodies a caricature of blackness that he’s not allowed to go outside of in order to be successful.

FW Yes, yes.

PH The minute that 50 Cent wants to make an album of polkas…

FW Exactly.

PH He’s done. Or he wants to do some strange avant-garde thing with Russian singers… can’t do it.

FW Yeah.

PH But he can be as Black as he wants within the narrow parameters of a blackness that’s defined from without.

FW But that’s what’s most important, a blackness that’s defined from without, yeah.

PH It’s stunning to me, you know, because the thing is that you know, artists (entertainers), I think knowingly capitulate to that, and it’s problematic because so much of our culture is informed by art (entertainment).

FW Yeah, yeah.

PH You know what I mean? You know, even if its incidental, you know, but it’s interesting because people don’t seem to recognize that it’s occurring.

FW Yeah, I mean, a guy I know is a Hollywood actor and I don’t know what he thinks about all this…

PH Don’t talk about it?

FW No, I don’t want to represent his views of anything.

PH Sure.

FW This guy has done TV shows and he’s done a lot of commercials and uh, small parts in movies and so, so he makes his money from this and it’s really good money. At the same time it seems to me that prison and Hollywood are one of the two places where everyone’s just really honest. My friend’s agent sent him to an audition for a comedic part, and they were telling him ‘try it again, try it again’, the casting director said no, you know, and they said ‘look, your agent said you were funny, what’s this?’ And he goes well I’m doing my best’, and she goes, ‘this is not Black funny’, you know. And he goes ‘what do you mean Black funny?’ I mean, because his humor is more I guess like Lenny Bruce you know, and she goes uh, ‘I think you know what I mean, Black funny. Let’s try it again’. And he goes, well this is what I do…And she was like I mean like Eddie Murphy. So can we take it again’, you know. He just didn’t get the part because he does narratives, it’s not Black… The funny thing I forgot, the punch line of this is he took me to Denzel Washington’s restaurant and there was a guy, behind the bar who was about the same height, 6-feet, and in his 30s, so they were both like 35, and he was tending bar, at Denzel Washington’s restaurant. And as we walked in, the guy looked at my friend, and my friend looked at the guy, and they looked at each other and said Black funny, you know. They had both gone to the same audition.

PH But you know, that is part of, that’s sort of, it’s a plantation mentality that gets played out, I mean, I’ve been dealing with that for years because you know, I’m also a musician and I’ve been able to have a project called Meridiem and it’s always me and some very interesting people, and it’s been very avant-garde. I mean the project has included people like Fred Frith and Bill Laswell, Vernon Reid of Living Color, and Trey Gunn from King Crimson. But I’m always looked at as the weird Black artist who does this avant-garde thing; they don’t know what to do. I had a guy one time from Melody Maker magazine you know, very prominent British magazine, say to me ‘if you were White they would be branding you the next boy genius, you would be like Beck’.

FW Wow.

PH They would just think it was weird and amazing but you’re Black so they keep wondering where the R&B is gonna come from.

FW Yeah, yeah.

PH So it’s an interesting thing, and we haven’t moved very far from it, you know, at all artistically.

FW I had so much, there was a lot of pushing back against this memoir (Incognegro) before I came to South End Press. One agent really liked it, she was a wonderful Black female agent, and the firm was owned by two white women and when they read it they were like fire him! One major New York house just loved the writing, but gave it to the sales force and they said there’s no way in hell we’re walking into Barnes and Noble with this….. Every time it hit upon some institutional gate, it was a problem. It wasn’t until these two Black women at South End Press were like okay; we’ll take it as is with your vision.

FW I had so much, there was a lot of pushing back against this memoir (Incognegro) before I came to South End Press. One agent really liked it, she was a wonderful Black female agent, and the firm was owned by two white women and when they read it they were like fire him! One major New York house just loved the writing, but gave it to the sales force and they said there’s no way in hell we’re walking into Barnes and Noble with this….. Every time it hit upon some institutional gate, it was a problem. It wasn’t until these two Black women at South End Press were like okay; we’ll take it as is with your vision.

PH Good for them.

FW Yeah, but it was, but it was two years of moving from $30,000 on the table for the advance to $1,500 when it finally got done.

PH You know, the thing that really gets me about this concerning the business is that people are not even acting in their own best self-interest when they make these decisions in my opinion. I mean, I look at Incognegro and I see above and beyond you know, the political orientation of it, the ANC, etc… it’s just a rollicking good yarn! I mean if I was Spike Lee, I’d be seeking the rights to the film.

FW Wow, that’s so nice. One guy, one Hollywood producer, heard me do a reading of some new work in Los Angeles in April, and he came to me and said ‘I really want to do this, let’s do it! You know how they talk…

PH Get all excited in the moment.

FW Yeah, exactly. And I was like okay, okay, well I’ll, we can talk a little bit later. Then as I was going into the theater to my reading, he says, but you know, we’re gonna have to cut out all the white women stuff you know……

PH That to me is a gross underestimation of the general public’s ability to deal with a great story.

FW Yeah.

PH There have been some films in the last four or five years that have been difficult stories that have caught on, but Hollywood shot callers have a short memory for that, they don’t see that, they wanna take a certain safe route to it.

FW Wow, thank you.

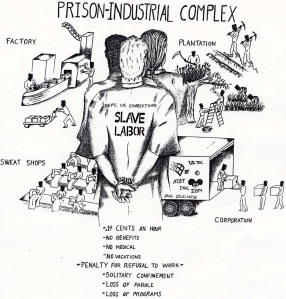

PH It’s a great story. In your book, in the recent book (Red White and Black, Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms), you speak about the prison industrial complex. We talk about the military industrial complex, etc. But not the prison industrial complex, and to me that’s very resonant, especially living in California which is the capitol of this sort of engagement, California and Texas.

FW Uh-huh.

PH You talk about it as being basically sort of a logical extension of this dynamic of the master-slave dyad. Maybe you can just talk a little bit more about.

FW Well, I think that the question of civil society, not all the questions but the truth of civil society, not the totality of it, but one of the concerns of civil society is how to contain “the Black”, and the answer to that question is like a hundred different splices of light going out in all directions. The professor uh, Desmond, I can’t remember his last name(A UCD prof that attended the lecture that afternoon), the older Black man who was speaking in the middle you know, he used to teach Economics here….he, talked about Jamestown and one of the things that I came across in the research for this book was a dissertation, a pro-slavery dissertation written by a White intellectual in 19-something in Virginia, and he was writing about the grain of sand, the germ, that creates the modern police force. And he locates this germ in the question of Black mobility. He charts how throughout the colonies all the way through the Civil War this thing that will become the modern police force, starts off as small collections of people just coming together to monitor the movement of Blacks. And that was really fascinating to me, you know. Obviously the police do a lot of other things today, they do the border patrol, and they do white collar crime…. but what his dissertation is saying is that the constituent element of policing is the maintenance of surveillance of Black bodies. I see the prison industrial complex as an extension of a kind of need, based upon what I would say is a fundamental anxiety concerning where is the Black and what is he or she doing.

PH There’s, a high degree of sensitivity to that. My father and I were just talking about this once, in the context of Rodney King, The LA riots, etc. My father made this beautiful analogy, he says you know, if you train a horse, if you train a horse, you know, and you tether him to a little peg and he gets used to it, then you can take it away, you can take the leash off of him and he’ll stand by the peg and he won’t run.

FW Yeah.

PH He said that’s how Blacks have learned to function in Los Angeles, they would not cross the line. They would come right up to the line, but not cross with violent intent, because we’re not supposed to be there and we know that deadly force will definitely ensue.

FW Yeah, yeah. There is a guy named Loïc Wacquant who also talks about the Black life being a life from birth to death of existing in what he calls a carcereal continuum (Editorial notes: original attribution of the term is to Foucault) and that different Black people live different modes of incarceration, but that imprisoning Black bodies is a project of civil society and for some people from the ghetto, their bodies take in this project full force, and others like you and I, meet the project when our car is pulled over by the police for being in the wrong neighborhood.

FW Yeah, yeah. There is a guy named Loïc Wacquant who also talks about the Black life being a life from birth to death of existing in what he calls a carcereal continuum (Editorial notes: original attribution of the term is to Foucault) and that different Black people live different modes of incarceration, but that imprisoning Black bodies is a project of civil society and for some people from the ghetto, their bodies take in this project full force, and others like you and I, meet the project when our car is pulled over by the police for being in the wrong neighborhood.

PH Speaking of Henry Louis Gates.

FW Exactly, exactly. Now as a Marxist explanation that I think is also prevalent but which is, I think, secondary to the collective unconscious explanation of it that I just gave you… Black people enter humanity, which is part of the premise of both my books, and humanity was demeaning. You know, I’m not the first person to say it, Baldwin just said everything in these two books in one sentence. We exist solely for this purpose of letting everyone know that they’re alive. You know, that’s my function. Because if someone loses their wife and their buddy and their job, and they are white, at the end of the day they can say at least I’m not a nigger.

PH That’s right.

FW And if you don’t have that at least I’m not a nigger then what you have is the end of the epistemological framework of modern life. We’d find ourselves self in a whole new episteme, and thought would have to be reorganized.

PH Absolutely. And I think that this is one of the primary mechanisms of resistance against something like reparations. Because if you take a step in the direction of something like reparations then you are recognizing the fundamental flaw in your orientation towards Black people.

FW Yes.

PH You’re recognizing it.

FW You’re recognizing it.

PH And they will not be recognize it.

FW No.

PH And it’s funny because until I read Red, White, and Black I hadn’t really formulated an opinion about reparations. I’m all for it man, they need to give me about $2.5 million tomorrow, you know, and it’s not even the money, we could all go out in the middle of the field and burn it, in fact that’s probably what you should do with it, go out and burn it because that’s not what it’s about. It ‘s processes, you know. And that’s another thing that your book helped me think through is what is the beginning of the discussion of processes for sort of, even just getting the ship up on its side because right now it’s upside down, so we don’t want to deal with these questions of truly ontological significance. That’s something that I’m kind of obsessed with right now is how do you actually have this discussion

FW I think that, as I said today, it’s such a mind blowing question and sometimes Percy I get so depressed. I just feel the weight of it, I come to school and I know that no other professor has this like fundamental question about how, about how to be in the world, And I’m really thankful for you and for a smattering of other people I’ve met out here because I haven’t really found this much on the West Coast. I like doing these interviews and these book talks mainly on the East Coast because…

PH There is a difference.

FW Yeah. I just find the Black people out there are, it’s kind of like what I was saying today about why Sacramento shocked me (Frank was shocked at the ethnic and economic diversity in Sacramento). After being on the East Coast, you know, it was like, normally California crowds are just so touchy-feely and the Black people in them are so isolated that they’re just trying to get along with the multicultural groove.

PH And you get that in San Francisco, in San Francisco you have this, what I call hyper real bohemianism amongst the Black left.

FW Yes.

PH So they really can’t talk about anything.

FW They can’t talk about anything. But you know, I’ve had things in Washington and Boston and New York and it’s, it kind of throws me back being in California just how intense Black people are (on the East Coast), and uncompromising and just hungry to have these discussions and just don’t care. You know, it’s like, I’ve had people ask me on the radio how to do guerilla warfare! (Mutual laughter). We were at WPFW in Washington, the FBI’s listening, they’re like how do you make a bomb? (Again, laughter). Metaphorically speaking—I’m mean they didn’t actually use those words, but they sounded ready for the get down.

PH It changes, exponentially, you know, with the more status and money that they have. California Blacks really get subsumed into this, especially if you’re upper middle class or above into this sort of disconnection that we seem to have on the West Coast. Now people always think that the East Coast is cold and disconnected, no, there’s more disconnection here just because of land and space and all this kind of stuff so you can just, you can afford to believe that everything’s cool. Whereas in New York City, you know man, you got a melting pot yeah, but still to this day you know that you can’t go to Bensonhurst, you can’t.

FW Yeah.

PH And if you’re a Black person you don’t go to Bensonhurst and they don’t go into Bed-Sty, they don’t do that, there’s this thing that’s there and it’s ever present and it’s real.

FW I did two radio shows with Black commentators who like you, just got to the heart of the matter. And then I did a reading discussion at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn which was…

PH I saw that.

FW Oh okay.

PH I actually watched that three nights ago.

FW Oh, the C-SPAN thing, yeah, that was actually recent.

PH That wasn’t at Medgar Evers?

FW It was but I had done one before two years ago by myself and that was so intense and I did one the next day, it was 70 White people at NYU. So I was like getting a real hit of this New York intensity and what really blew my mind was that the sophistication and the anger combined…. just ordinary people politically sophisticated and angry.

PH When you did the talk at NYU you know, when it was predominately a White audience…I would presume to think that they might even be more transparent and ask difficult questions, or questions that might even expose their biases more so than you would think…

FW Yes, yeah.

PH Was that sort of your experience?

FW Yes, I felt that a lot of people at NYU were, were, because New Yorkers like get in your face, I mean, they don’t have no California nice going on.

PH No.

FW And so, so, so foolish me not remembering when I used to live in New York what it’s all about you know, I had been at Medgar Evers the night before and, then before that I think it was Harlem, the Brecht forum which was a mix of Black, White, and Asian, Marxists, etc, and then NYU. So at Medgar Evers, what was happening was that, I would say out of 70 people, 50 were we’re actually going to vote for Obama but all 70 people were against the United States as a concept. I mean, in other words they were all politically militant, some were nurses, some were lawyers that were trade unionists, perhaps random students, and people that were unemployed. But no one tried to shut down what was happening in terms of this like ongoing spontaneous critique about how unethical America was as a place, which was what I had introduced. At NYU the young people there were demonstrably bored with me! They put their feet up on the back of chairs, it was like who is this fool? I mean they were getting up and leaving and so on, so it was quite, you know it was quite…

PH Right.

FW Everyone’s on the same page regardless of what they were gonna do in two days time when the election came. Okay? And at the book signing, I mean brothers and sisters like took up chairs next to me to tell me their horror stories about what’s happening in their profession, you know. And I had said at one point when someone asked me my feelings, and I said I’m not a Democrat or Republican, nor an American, you know, and this nurse, this older woman nurse walked up to me and said ‘I want to talk to you about what you said’ and I thought oh no, here it comes.

PH She’s gonna smack me.

FW And she said “I have thought that all my life but I don’t say that at the hospital. I am so glad you said it tonight.” I hate this country but I just can’t, I can’t say it at the hospital, I thank you so much for having said that’.

PH And I think there’s a lot of interesting impetus for that. It’s a very complex set of emotions for Black people around this country, because one can say I hate this place and you mean that on a profoundly real level.

FW Uh-huh.

PH And on another level, it’s not your experience or what you mean…

FW Yeah.

PH Because you know, you have these contradictions that go on…. do you remember the Public Enemy song Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos?

FW Yeah.

PH Because what does he say in that one line, he says something about “because I’m a Black man and I can never be a citizen’.

FW Yeah.

PH But I, mean Chuck D, his Dad was a dentist or something, he had this certain life but then he has this other experience, you know, that co-exists sort of side by side with that.

FW Well my father, he rose to the Vice President of the University of Minnesota, very involved in the Democratic Party, major lobbyist you know, for the University of Minnesota, and on boards of these corporations, same with my mother, and you know, the other day, he had this problem. He’s almost 80 and had a complicated issue with his shoulder and needed to go for surgery. When he goes to the University Hospital they treat him like a king, I mean, there’s just, the University of Minnesota owns, has a hospital on campus where he’s treated like a king, but it also has a University hospital in Fairview in the suburbs where the doctors are not professors and out of convenience because he lived near there he just went there to the suburban version, And they treated him like a n-i-g-g-e-r for maybe the first time in 30 years and what he didn’t, I mean, if he had gone in and said uh, I’m Frank Wilderson, former Vice President of the University and da-da-da, then they would have treated him right. And they left him on a stretcher, on the gurney after the operation in the hallway for five hours and…

PH It’s kind of funny you say that because that’s how my grandfather died.

FW Well, he almost died, the blood clot went from his shoulder to his lungs, and my mother couldn’t get anybody to pay attention to him in the hallway of a major, major suburban hospital.

PH Did they catch shit for it after…

FW Well, I’m hoping my parents will sue. And on top of that they tried to push him out of the hospital early, you know, and finally, my reading of the story is that someone from the main University hospital called them and said basically, this is not a Negro, this is our Negro.

PH Yeah.

FW You know, this is our prized Negro, what are you doing, you know….then it all changed.

PH But that’s the unfortunate reality, like in a Black ghetto having to be subjected to a certain type of brutarian experience regarding race that we don’t have to suffer every day.

FW Right.

PH But when we do come into contact with it, the apparatus, it’s like that, and often the answer is you get a pass because of your context.

FW Yeah.

PH We’ll give you a momentary pass and we’ll give you a contextual pass.

FW Right.

PH And the fact that someone has to give you a pass…

FW Yes.

PH …is just as oppressive as if they didn’t.

FW Yeah.

PH It’s hard for people to understand. I went to university at a place called Harding University. Have you heard of it?

FW Where is that?

PH It’s in Arkansas.

FW Okay.

PH And it’s a small liberal arts Church of Christ university and I went there in 1979. When I was a freshman there were 180 Black students on campus and 155 of us were athletes. Seriously.

PH And it’s a small liberal arts Church of Christ university and I went there in 1979. When I was a freshman there were 180 Black students on campus and 155 of us were athletes. Seriously.

FW That’s amazing.

PH So those experiences, I mean, that whole process became very alive for me at that time you know, when you really could realize the whole contextual exemption from Blackness because you’re smart, and middle class.

PH On another note, regarding your contrast of the thought of Fanon and Lacan on these issues, I always thought Lacan was a Buddhist…..

FW Yes, yes, yes.

PH He’s a Buddhist. I never really sort of questioned his a priori assumptions.

FW You know, someone accused me of being cavalier with that, and my point is that I’m not cavalier, I’ve been in psychoanalysis for over 10 years and I’ve just left it, not that I’m cured, but just because it’s so expensive and I’m not sure…

PH Yeah, it’s expensive.

FW But I’m saying that this doesn’t matter in an essential way; I’m not saying that I wanna be crazy walking around. When I first came back (from South Africa), I was going crazy….

PH Well you might have had a touch of PTSD as well.

FW Yeah I really did, I really did. And I had physical ailments that were really psychosomatic; I used a cane for a while. It was just hard being back. My brother, lovely and wonderful (we grew up separately because he went to private schools in the suburb and he’s 10 years younger than me) he allowed me to live at his house. I was teaching at Compton Unified School District which, I didn’t know how it could be worse than Soweto, but it is.

PH Compton’s pretty bad.

FW Yeah…. and so trying to find psychoanalysts you know, when I finally moved to Berkeley at the end of ’97, what struck me is that there were very few Black people in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis then. And when I went to White Therapists to interview them, I found a tension there in that they were a little too anxious about bringing the whole racial component into the analyst room. And then when I went to some Blacks, maybe the wrong ones, they were a little too anxious about wanting to make me better now because seeing how crazy I was and crying uncontrollably and needing anti-depressants and so on, I knew that they were suffering my suffering right here in this room, but I felt that the help was coming too quickly because they wanted me to be safe. So I finally end up with this white guy which is very problematic for about two years only because he said the least of anybody that I had interviewed. And what I kind of got through him was that he could help me not go into psychosis and to manage neurosis but at the end of the day his other clients had contemporaries in the world and I did not, and that was fundamental, it’s like my dad’s situation. My dad thought he had contemporaries but when he went to the wrong hospital he realized that he was just Black you know, and that was the one thing that can’t be solved in the psychoanalytic encounter.

PH No, it can’t.

FW So, I stayed with this guy for a while, a long while, because what I was able to do through him was hear myself talk over 10 years and work out a lot of the stuff in this book without him pushing back like it’s not about race, it’s not about race, it’s not about race which was what a lot of the Whites were doing that I interviewed. The Blacks were saying this is what you gotta do to stay alive, you know, that kind of thing. Ultimately we parted and I’m not necessarily sane or anything like that, but I did get a book, you know, and uh, and he learned a lot, he learned a lot about the limits of his profession through me.

PH Yeah, White psychotherapists often struggle profoundly with something that is jammed into the brain of every psychotherapist, and that is cultural formulation, cultural formulation, cultural formulation.

FW Interesting.

PH It’s essential to not deny you know, from whence a person comes, you must look at the universal breadth of their culture. But what happens is, you get taught, it’s an academic nail in the head, um, but what happens is it’s the way that being able to perform a useful cultural formulation gets stuck in very small parameters, i.e. the color of one’s skin, are you a male or a female, these sorts of things. What gets negated is the sort of functional breadth of experience. What I mean by that, and this happens to Blacks like you and I quite often, is that we share the fact that we were raised middle class people.

FW Yeah.

PH There is an element of the formulation of culture within us that is informed by that, inescapable. We did not grow up in Harlem or Compton.

FW Exactly.

PH But see what happens is that the White psychotherapists are not prepared to deal with the Black person who is possessive of those types of nuances.

FW Yes, exactly.

PH Or the Indian person or the Asian person or the White person for that matter because the training is not sufficient to the task of taking a more global view of certain human suffering. So when you found this guy he was a guy that didn’t suffer from that particular malady, he didn’t have to perseverate on that issue.

FW Yes, yeah.

PH Good therapist, Black, White, or otherwise.

FW Yeah.

PH You deal with what presents and then you move on. But that’s what you were encountering and many people encounter that in therapy and I see it as a flaw in the educational preparation and process. In fact I’m involved in a project right now, and one of the things we’re taking a look at is this flawed cultural formulation.

Your experience with the Black therapists was a very common experience. I think Black people in America have a tendency to have a profound fear and distrust of mental illness.

FW Yeah, yeah.

PH Because it’s been used as a weapon. Black psychoanalysts man, they want to be the guardians of the gate, they want to help you get past it, you’re not crazy, I don’t care if you’ve been told you’re crazy, you’re not crazy and this is how we’re gonna show you you’re not crazy, we’re gonna do it and they have a tendency to be very functional, very outcome oriented…

FW That’s the word, functional and outcome.

PH Yes, very constructed you know, and the better they are the more they are that way.

FW Yeah, yeah.

PH You know, so actually I’ve been doing some writing about this very issue so I’m glad you brought that up. But yeah, your experience just to let you know Frank, very typical.

FW I appreciate that. I was feeling guilty. You know, I was like you know, I gotta use a Black person but this is, it’s not that simple that we, we can’t like make a life plan in four sessions you know.

PH And that was extremely typical you know, so that’s not your issue. Well, I just have a couple more questions here and I did send you some email questions so you can get to them…

FW I’ll definitely get to them.

PH How do you, how do you see it, what is the role, what can be a role of spirituality or religion you know, in this human drama, in this struggle, or is there a role?

FW Um…

PH How do you see it?

FW Well I have two contradictory answers to that.

PH Okay.

FW Uh, I’ll try to put them together.

PH Ok.

FW What I’m trying to say is at the level of relations of power, what does it mean to be Black? In the way that Marx said, at the level of the relations of power what does it mean to be a worker? Well, what it means to be a worker is that one goes through one’s life captive to two questions; how long will I have to work and how much will I have to do? And that the only things that change one’s life are the particulars of those questions when you change jobs, when you earn more money, etc., etc. But why he calls capitalism unethical is because those are paradigmatic questions for one class of people, and the other class of people doesn’t have those questions.

And so what I think is that there’s so much talk about hybridity, diversity, and possibility that what I want to contribute to the world is a text about impossibility, Blackness as a space of impossibility. Now having said that, there are things I do to manage myself, to help me be okay, know what the world is saying or whatever, in a place where everyone sees me as their object, you know. One of the things I said in psychoanalysis and another thing that I do is consult regularly with a teacher, Babalawo, who consults ancestors to help me. But I’m, I’m a little cautious and uh, uncomfortable with incorporating that into my political analysis and my political philosophy. One, because I don’t write about, I don’t write the answer to Lenin’s question, what is to be done? I think, I believe that the liberation of Black people is tantamount to moving into an epistemology that we cannot imagine. Once Blacks become incorporated and recognized I don’t think we have the language or the concepts to think of what that is. It’s not like moving from Capitalism to Communism, it’s like the end of the world.

PH It’s like moving to Mars.

FW It’s like moving to Mars.

PH You know, it’s a contextual dilemma. You know, and that’s a good enough answer. I think that’s great. Um, what else, did I have anything else? Actually I had another question but I don’t think I want to ask it now…

FW Tell me what it was.

PH I have a little Oprah problem. I don’t know, I just, I always ask, I always like to ask, especially Black artists what they think about the sort of sociological significance of Oprah and how she’s impacted, you know, the whole landscape of sort of aesthetic and artistic acceptance of Black output you know, because she’s monolithic.

FW Yeah.

PH But we don’t have to get into that.

FW Well, you know, um, uh, Charles Burnett, he was doing a screening of Killer of Sheep and some other movie at UC Berkeley, he was at the Pacific Film Archives giving a talk. And someone in the audience asked him about a film that Oprah had produced and he said working for Oprah is worse than working for the Klan. I was like what!? I kind of got whiplash.

FW Well, you know, um, uh, Charles Burnett, he was doing a screening of Killer of Sheep and some other movie at UC Berkeley, he was at the Pacific Film Archives giving a talk. And someone in the audience asked him about a film that Oprah had produced and he said working for Oprah is worse than working for the Klan. I was like what!? I kind of got whiplash.

PH Did he go on or did he just stop?

FW He didn’t go into great detail but he likened to a problem that he had spoken about a few minutes earlier but he said he made a movie called Night John about a slave who runs away and re-enslaves himself so that he can teach people to read and find his wife.

PH Right.

FW And he said Charles Lumbly, who lives in Berkeley played in Night Job, and he talked about how unsentimental and how raw and true he wanted that film to be….

PH Right. And they (Disney) killed it.

FW And they just kept reaching their hands into, they gave him, there’s a little girl in the film, I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it but it’s a really interesting film. There’s a little girl and he had a little girl that he wanted as a slave girl and they got this other like, Disney slave girl and he was just fighting with them all the time, you know. And so his point was that, that working for Oprah was worse than that because she, her interventions are more in line with White civil society.

PH Like I said I got a little problem…I remember walking out of the Color Purple.

FW Yes.

PH To me one of the most profoundly disgusting horrendous pieces of tripe that I’ve ever had to deal with. And there you got a combination of Oprah and Spielberg. Spielberg who is highly invested in this… people want to compare him to Frank Capra, I’m like don’t compare him to Frank Capra.

FW No, no.

PH Capra had a sense of irony about this stuff, you know, I mean he really did.

FW Yeah, yeah.

PH I mean he knew that everything was so shiny and there was always some weird thing that sort of came in there with Capra. But you know, that sort of Spielbergian vision, you know, coupled with her stuff has not been good for art.

FW No, it hasn’t.

PH And they both have like a monstrous amount of power, but.

FW My acupuncturist, he’s a White guy and he means really well, wonderful guy but he keeps saying to me, this is such a great book, why doesn’t Oprah want you on?

PH Oprah would never let you on her…

FW I’m like Jay, Jay!, I got on NPR and the day after they had transcribed the entire thing on a right wing blog and someone was, people were writing in about why they need to close down NPR because of this interview….

PH Oh yeah.

FW And it was, it was just, and then I was supposed to be on another…

PH To bad Moyers retired, he’d probably…

FW He might have. But I was supposed to be on another public radio station, NPR station in Minnesota and the day before the interview the producer called me and said we just need to know, did you kill anybody(in South Africa). And I said the book is about the relations and structural violence and personal violence and I do not want to talk about violence at the level of personal guilt. I want to talk about it in a different way. She says ‘you gotta answer my question’. And I said when, you’ve interviewed former members of the CIA, um, military officials…

PH And plus that’s nuts because you know what? If you killed somebody and and they knew about it, as soon as you came back to this country you’d be in jail.

FW I’d be in jail.

PH You know.

FW And I said to her um, do you say that to your son or daughter when they come back from Iraq? You know, is that a prerequisite for them sitting down at Thanksgiving with you? Is this a prerequisite for you having police officials on your show?

PH It was a moral conundrum for that producer.

FW Yeah.

PH It didn’t have anything to do with them having to do a certain type of due diligence.

FW And I said well, that would mean that I would have to in some way renunciate the idea of our struggle for people who are suffering and the book doesn’t do that you know, and I said why can’t we have a conversation about that question on the air tomorrow? And she said ‘I’m sorry, you know, you either answer the question or we have to call the show off.’ So they called it off.

PH And this is probably a show that had somewhat of a leftist image.

FW Yeah, yeah.

PH There you go.

Hi there, I found your website via Google even as searching for a similar subject,

your site got here up, it looks great. I’ve bookmarked it in

my google bookmarks.

Hello there, simply become alert to your weblog

thru Google, and located that it’s truly informative. I am going to be careful

for brussels. I’ll appreciate if you happen to proceed this in future.

Lots of folks will probably be benefited from your writing.

Cheers!

Pingback: The Netherlands and Its Discontents, or: How White Dutch Folks Started Worrying and Urged ‘Us’ to Take Rioters Seriously | Processed Life